08 Sep The potential for teleworking in Europe and the risk of a new digital divide

The growth in teleworking seen during the Covid-19 crisis has been strongly skewed towards highly paid occupations and white-collar employment, raising concerns about the emergence of a new divide between those who can work remotely and those who cannot. Nonetheless, enforced closures of economic activities due to confinement measures resulted in many new teleworkers amongst low and mid-level clerical and administrative workers who previously had limited access to this working arrangement. This column presents new estimates of the share of teleworkable employment in the EU and discusses factors determining the gap between actual and potential teleworking – including elements of work organisation. It also discusses how telework patterns could develop in the future and related policy implications.

While a teleworking revolution had been predicted intermittently for over four decades, it never really materialised. Indeed, figures from representative labour force surveys show that until the advent of the Covid-19 crisis, only around one in twenty people employed in the EU27 usually worked from home in 2019 – a share that had remained rather constant since 2009. The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting confinement measures put in place to slow down the spread of the virus suddenly changed all this, out of necessity. During the first semester of 2020, working from home has become the customary mode for millions of workers in the EU and around the world.

The important role of telework in preserving jobs and production in the context of the Covid-19 crisis has been highlighted by the European Commission in its recent communication on the 2020 country-specific recommendations (European Commission 2020). Yet, teleworking is not for everybody, raising the possibility of a new divide between those who can telework and those who cannot. Against this background, identifying how many, and which, jobs can be performed remotely has become a key factor to understand the pandemic’s economic and distributional consequences.

‘Teleworkability’ as technical feasibility (but not only)

In a recent report jointly prepared by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission and Eurofound (Sostero et al. 2020), we present and discuss the large differences in the prevalence of teleworking across jobs in Europe before and during the Covid-19 outbreak. In particular, by anchoring our analysis to previous work proposed by Fernández-Macías and Bisello (2020), we try to identify which factors contribute to make a job ‘teleworkable’ and to what extent. Our work contributes to the growing debate on the potential for remote work (Dingel and Neiman 2020, Berg et al. 2020) by providing an explicit theoretical framework to the concept of ‘teleworkability’ and estimations based on European occupational data.

To do so, we looked at the task profile of more than 130 occupations, using occupational task descriptions from the Italian Indagine Campionaria delle Professioni, with additional indicators from the European Working Conditions survey. Since with current technology, the physical manipulation of objects is the real bottleneck to remote working, we measured to what extent workers in each occupation need to perform physical tasks such as moving objects, inspecting equipment, or operating vehicles. Jobs that require a significant amount of physical tasks were classified as non-teleworkable, while all other jobs were considered technically teleworkable.

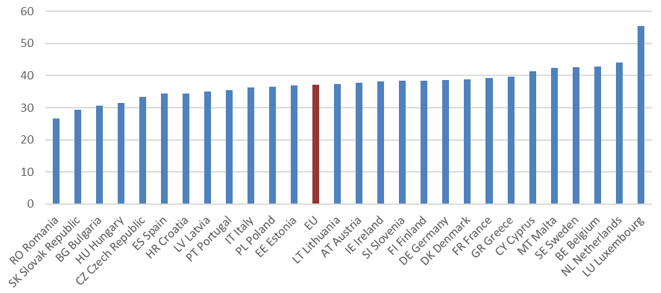

Applying this classification to occupational employment data, we estimate that 37% of dependent employment in the EU27 can technically be carried out remotely. This estimate is very close to those indicated in real-time surveys conducted during the Covid-19 crisis, notably Eurofound’s “Living, Working and Covid-19” e-survey (Eurofound 2020). Our estimates of the fraction of teleworkable employment range from 35% to 41% in two thirds of EU countries, with the highest value in Luxembourg (54%) and the lowest in Romania (27%) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Percentage of employees in teleworkable occupations by member state, EU27

Note: Employees only.

Source: Authors’ calculations from EU LFS.

Overall, these estimates likely provide an ‘upper bound’ on the percentage of jobs that can be done remotely in an efficient way. The majority of teleworkable jobs requires extensive social interaction, which often make working remotely sub-optimal. Even the most sophisticated videoconference systems are unlikely to match the quality of face-to-face interactions (e.g. Schoenenberg et al. 2014), be it for medical advice, counselling, teaching, and so on.

On this basis, we estimate that only 13% of employment in Europe is in teleworkable occupations that involve no or limited social tasks (e.g. selling, teaching, caring for others, working with the public) and can in principle be carried out remotely with no or limited loss of quality. The remaining 24% of technically teleworkable jobs involve extensive social interaction and thus they can only be partially provided remotely (for instance, for some but not all tasks) without a significant loss in service quality.

What jobs can be done from home?

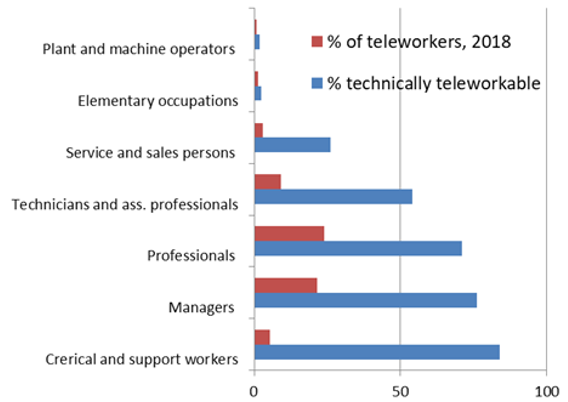

When breaking down figures of technical teleworkability by broad occupation group (see Figure 2), a first striking difference emerges between white-collar and blue-collar work, with the latter being much less teleworkable mainly due to the physical requirements of the jobs and the associated place dependence.

Another very interesting result concerns the occupational distribution of the gap between actual and potential teleworking, with the highest figure observed for lower-level white-collar occupations. Indeed, although the characteristics of the job are such that almost all (84%) clerical support workers could telework, only 5% of them had worked from home before the Covid-19 crisis. Such findings would suggest that, beyond technical feasibility, differences in access to teleworking across occupations also depend on aspects related to the organisation of work and the position in the occupational hierarchy (and related privileges), rather than the task composition of the job as such. As already argued in an earlier Vox column (Fernández-Macías and Bisello 2016), work organisation is a crucial aspect of the task profile of occupations which can also affect access to teleworking in particular cases. The fact that managers typically enjoy more autonomy and are subject to less monitoring of their work effort than secretaries is probably related to the much larger prevalence of teleworking for managers before the Covid-19 crisis, even if the work of secretaries is technically more teleworkable. The sudden extension of teleworking to occupations where it was previously less prevalent is probably inducing important changes in work organisation, including a growing utilisation of digital tools for the remote control and monitoring of work effort.

Figure 2 Teleworkability and actual teleworking as a share of employment by broad occupation group, EU27

Note: Employees only.

Source: Authors’ calculations from EU LFS.

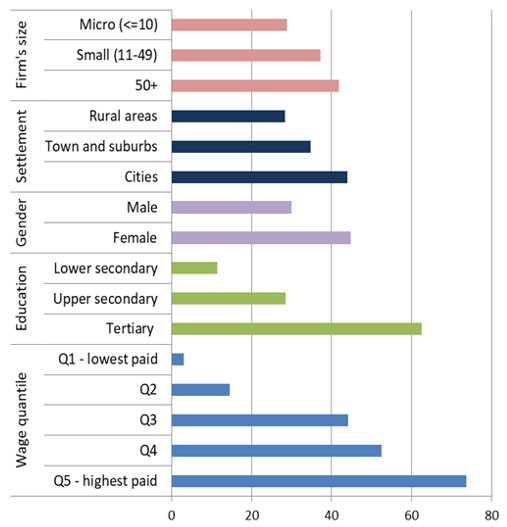

When looking at the socioeconomic profile of workers in teleworkable occupations, stark differences emerge between high- and low-paid workers, with three-quarters (74%) of those in jobs in the highest paying wage quintile who can telework, compared to only 3% of those in the lowest quintile (see Figure 3). A divide is also seen when looking at the differentiation by educational qualification, with around 66% of tertiary education graduates working in teleworkable occupations, against a much smaller share of those with lower levels of qualification. Gender differences also emerge, with a much higher share of women than men (45% compared to 30%) in teleworkable occupations. This reflects to some extent to patterns of sectoral segregation – as women are under-represented in sectors such as agriculture, mining, manufacturing, utilities and construction with limited teleworkability – but also differences in the job profiles even within male-dominated sectors, with women being more likely to be in office-based, secretarial or administrative jobs which are more amenable to remote working.

Meanwhile, more than 40% of employees living in cities are in teleworkable occupations, against fewer than 30% of those living in rural areas, which reflects the fact that cities have larger fraction of employment in knowledge- and ICT-intensive occupations than towns or rural areas. Employees in medium and large firms are also significantly more likely to be in teleworkable occupations than those working in micro-enterprises.

Figure 3 Employees in teleworkable occupations by workers’ characteristics, EU-27 (%)

Note: Employees only. Job-wage quintiles based on author’s calculations of SES 2014 data.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on EU LFS and Structure of Earnings Survey.

Post-Covid-19 teleworking patterns: A new digital divide?

What are the implications of the ongoing ad hoc experiment in mass teleworking for the future of work? Evidence from our study suggests that access to teleworking during the pandemic has become more evenly distributed within white-collar occupations, resulting in new possibilities amongst low- and mid-level clerical and administrative workers. In teleworking, the monitoring of work effort is much more difficult and thus requires a higher level of trust. In this sense, the expansion of teleworking could shift cultural and organisational norms, expanding levels of work autonomy and making more accessible what so far has often been a privilege associated with high professional status. Yet, firms’ and workers’ lack of affinities with digital tools and prior experience with remote working arrangements may limit its uptake and effectiveness (Milasi et al. 2020). There is also the danger that organisations respond to this challenge by using intrusive digital tools for remotely monitoring work effort, which has troubling implications in terms of job quality, privacy and autonomy.

At the same time, a new divide between those who can telework and those who cannot has emerged. Indeed, dramatic differences can be observed in teleworkability by wages and by education level. Experienced employees in white-collar occupations, often in knowledge-based services, reported the highest incidence of teleworking during Covid-19. In order to avoid a teleworking divide, access to remote working arrangements should be facilitated also among younger and lower-qualified employees. As workers with strong digital skills are arguably better positioned to respond to the demands of remote working during the current crisis, it is important that extensive training opportunities are offered. However, as long as the bottleneck of physical tasks remains (jobs with significant manual task content cannot be teleworked), a broad expansion of telework would unavoidably increase the social distance between those that need to work with their hands in particular places and those that can provide intellectual and social services from any place.

References

Berg, J, F Bonnet and S Soares (2020), “Working from home: Estimating the worldwide potential”, VoxEU.org, 11 May.

Bisello, M and E Fernandez-Macias (2020), “A Taxonomy of Tasks for Assessing the Impact of New Technologies on Work”, JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology 2020/04, JRC120618, European Commission.

Dingel, J and B Neiman (2020), “How many jobs can be done at home?”, VoxEU.org, 7 April.

Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19: First findings – April 2020, Dublin.

European Commission (2020), 2020 European Semester: Country-specific recommendations.

Fernandez-Macias, E and M Bisello (2016), “A framework for measuring tasks across occupations”, VoxEU.org, 25 September.

Milasi S, I González-Vázquez and E Fernandez-Macias (2020), “Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: where we were, where we head to”, JRC Science for Policy Brief.

Schoenenberg, K, A Raake and J Koeppe (2014), “Why are you so slow? Misattribution of transmission delay to attributes of the conversation partner at the far-end”, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 72(5): 477-487.

Sostero M, S Milasi, J Hurley, E Fernandez-Macias and M Bisello (2020), “Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: a new digital divide?”, JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology 2020/05, JRC121193, European Commission.